What happens when we're not all human Part I

- Sandy Siegel

- Mar 14, 2020

- 17 min read

The following blog is posted as a four-part series.

Spending time at the Smithsonian Museum makes one proud to be an American. The Smithsonian is our national museum, and it is spectacular. Nancy and I had a free weekend this past October and decided to spend it in Washington DC at the museums. On Friday evening, we went to the mall and got to appreciate the Capital Building and the monuments at night. Beautiful and inspiring. Over the weekend, we visited almost all the monuments, went to the National Gallery, the Botanical Gardens, and the Hirshhorn.

We spent the most time at the Holocaust Museum, The National Museum of African American History and Culture and the National Museum of the American Indian. We started at the Holocaust museum when it opened on Saturday morning. This was going to be the most personal experience for us, because we are Jewish. Neither of us had previously been to this museum. We both had done lots of reading about the Holocaust, and watched lots of documentaries and movies over the years, so none of the history was going to be a surprise for us. We understood the anti-Semitism that was rampant in Europe, and the events that led to Hitler's rise to power. We were painfully aware of the camps and the loss of so many precious lives. I remember some of my Hebrew school teachers were survivors. The parents of some of my childhood friends were survivors. There was no mystery about where we were going and what we were going to be feeling.

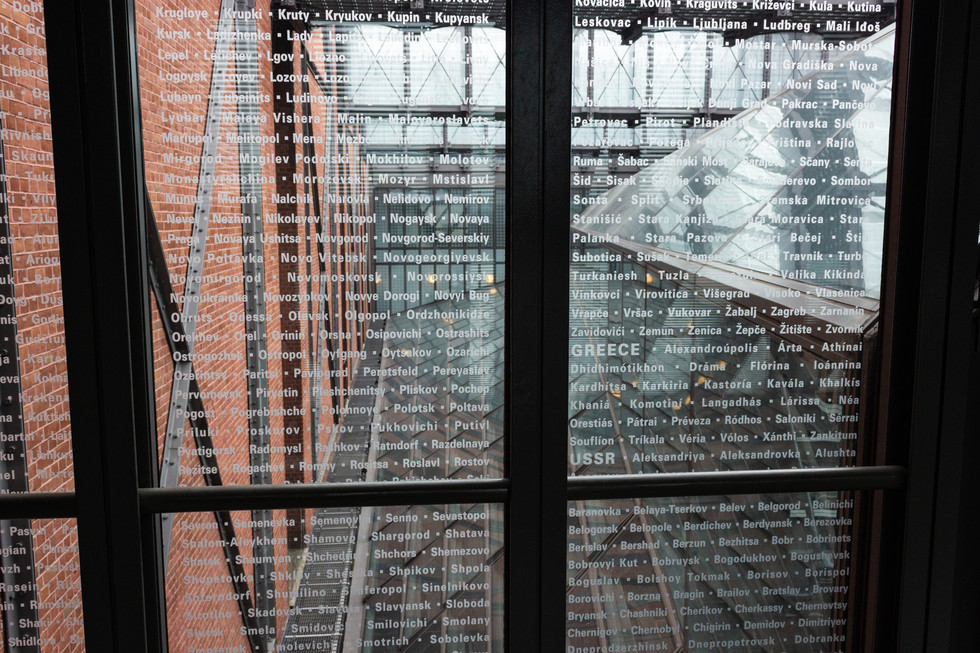

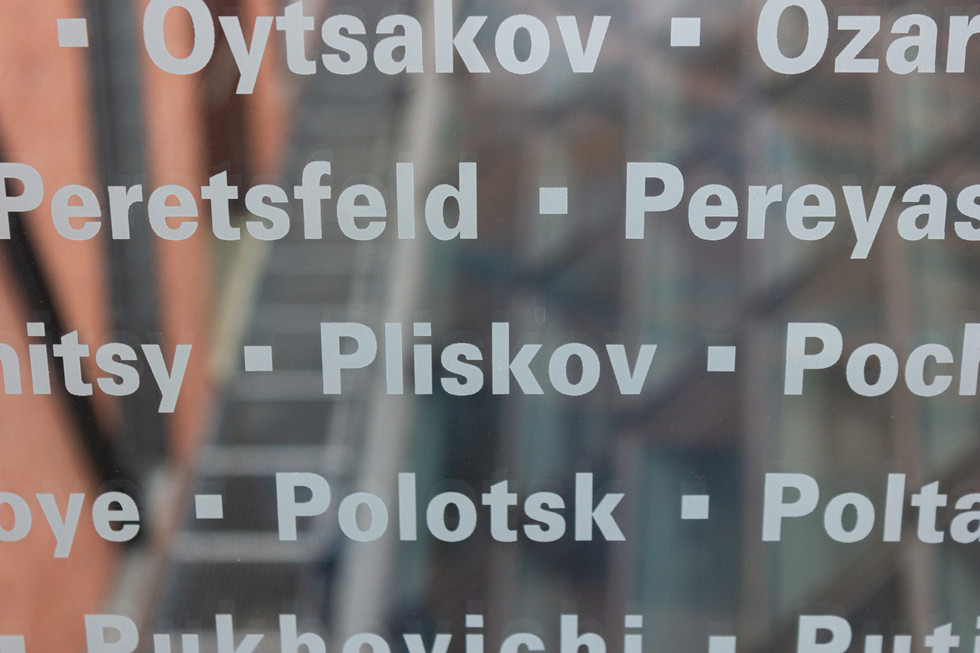

I was prepared to be painfully sad. I was not prepared to be devastated. We were about halfway through the exhibit when we arrived at a hallway connecting wings of the museum. There was a plaque at the entrance of the hallway indicating that the wall of glass had the names of villages and towns etched into them. These were the names of places that had been wiped out during the Holocaust. They no longer existed. The names were organized alphabetically by country. My Zadie was from Tetiev. I knew it still existed because I'd seen photographs of the town on the internet. It would be hard to imagine that a single Jew was left there after the pogroms, but the buildings, streets and descendants of the people who raped and pillaged remained. My Bubby was from Pliskov. It was a much smaller village, and I had no idea what happened to it. My Bubby was the only one of her family that made it to the United States. Her coming here is a remarkable story. I should write a blog about it sometime. I am named for my Bubby's two brothers, Srul and Yosef. I looked through all the names covering the walls, and felt such sadness reflecting on the lives lost behind each of those names. And then I saw it. I stood with my head down and wept.

The village was no more. The people were no more.

My Bubby lost contact with her family after she arrived in the United States. The loss of her family, our family, was a constant sadness in her life. She knew her brothers were gone. They might have been killed at Babi Yar or it is possible that they were starved to death by Stalin's imposed famine in the early 1930s.

One of the more profound experiences for me was the room filled from floor to ceiling with photographs from one of the shtetls. The room told the stories of the lives of the villagers; a village that no longer existed after the Holocaust. The photographs could have been of my family. The photographs could have been from Pliskov or Tetiev. So many lives taken. A culture destroyed.

We left the Holocaust museum emotionally drained. It is hard to find an American Jewish family that hasn’t been touched in very personal ways by the pogroms and the Holocaust.

We next walked across the mall to The National Museum of African American History and Culture. You need a timed ticket to this museum which we didn't have, because we had no idea when we were going to arrive. There was a representative to the museum helping people obtain tickets via an online process. I took out my phone, downloaded the app, and went through the process. Miraculously, I was able to get two tickets.

The museum presents a comprehensive history of slavery in the Americas. The museum also includes a history of African Americans in our society and culture. There is so much to read and to see. We would have appreciated the museum so much more if we had the opportunity to take our time to read our way through the exhibits. We were not able to because it was packed to the gills. Often, you had to move through an exhibit before you were ready to move on, just because you were caught in the crowd moving downstream. We were able to spend enough time in the museum to take in the history; a shameful reminder of the impact that slavery and the Jim Crow laws have had on our society and culture.

Hours in the Holocaust and African American Museums. Emotionally brutal. We spent the rest of Saturday walking around the mall. The World War II Memorial, the Vietnam Memorial, the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Monument. Such beautiful and meaningful structures. So much history. So many tourists.

We began Sunday with the Museum of the American Indians. It was a beautiful sunny day. The building and the grounds are so well done. Meaningful and beautiful. If I was king of the museum, I would have done it differently. I would have organized the museum using Alfred Kroeber's culture areas in the America's. It is an excellent way to describe the traditional ways of life of the many tribes across north, central and south America. I then would have presented a comprehensive history of the relationship between the tribes and the greater American society and the history of the federal government and the American Indian. Alas, I'm not in charge of anything.

I went to college for 14 years to become a Native American specialist. I studied under Dr. George Fathauer at Miami University. Dr. Fathauer was a cultural anthropologist and Native American specialist. My interests were strongly influenced by my work with this exceptional professor. I received a master's degree and doctorate from The Ohio State University in Cultural Anthropology. I did two years of fieldwork on the Fort Belknap Reservation with the Aaniiih or White Clay People. They were traditionally a very typical plains tribe.

I can summarize our (American society) treatment of the Native American tribes succinctly. We screwed these people in every way imaginable, and they suffer the consequences of their relationship with us individually and collectively as tribes every single day.

As we left the museum, Nancy and I looked at each other feeling totally dejected. I announced to her that we totally suck.

Jews. African Americans. Native Americans. Our histories and our cultures were so markedly different, and yet, there is a common and significant thread that runs through the fabric of our histories and our present lives. We lived in societies that did not consider us human.

You don't send humans to the crematoria. You don't take humans as slaves. You don't remove humans from their land and their homes, kill off their food supply, take children away from parents and send them to boarding schools in order to systematically and very intentionally destroy their languages and cultures. Not human.

This phenomenon wasn't invented by western civilization or in America. It is, in fact, as old as humanity, and likely older. It depends on how human you want to consider Homo neanderthalensis. I know this to be the case because I've read the entire Clan of the Cave Bear series. In many societies, the traditional name used for the group translates as the real people or the real human beings. Jews are referred to as The Chosen People (the people who G-d chose to give the Torah). There isn't a People on the face of the earth who don't believe that they are the chosen people or the real people or the real human beings. Why is that?

Our language and culture are learned. We are born with a blank slate. We are born with the physiological capacity for language, but the one you are going to understand and speak is going to be a function of the family you are born into and what you are taught. Culture is going to work the same way. The rules for who is a relative and who are not relatives will be learned. The social rules for defining good and bad behavior are learned. Your origin myths and your historical myths are learned. What you consider food and what is consider not edible or repulsive is learned. Whether you believe in G-d or gods, and the nature of the Great Spirit or spirits, whether there is an afterlife is learned. There is nothing absolute about any of these beliefs. They all exist for you from the accident of your birth. I was born to my parents and thus learned American culture, became Jewish, and learned American English as my first language. If I was taken from my parents at birth and given to a Japanese family, I would have learned Japanese language and culture, and would have practiced Shinto and/or Buddhism.

It is a function of the way we learn culture, that humans in every society become ethnocentric. Ethnocentrism involves the way we think about our own culture, and how we evaluate other societies and cultures. We believe that our culture is natural, superior and right and that societies with different cultures are less natural, inferior and, yes, wrong. We don't really think about it. We just feel this way.

You might be able to have an objective conversation about whether it is possible to shoehorn a tiny bit of democratic socialism into a market economy. When it comes to faith issues or values, one must wholeheartedly and unequivocally buy into the whole megillah. We need to have people learn the intangible elements of culture as though they come directly from the burning bush. There is no wiggle room. We learn these elements in such a way that they feel as though they are biological in origin. It feels as though the belief in one supreme being who created the heavens and earth in six days and then rested on the seventh is genetically wired into our brains. Most of our beliefs, guiding values and world view, social rules, customs, and rituals feel this way. They are not in any way biological. They are entirely learned.

I've spent a significant portion of my life studying cultures other than the one I was born into and learned. I devoted fourteen years of my life getting a doctorate in the non-western peoples and cultures of the planet earth. I lived and worked on a reservation for two years among three different plains tribes, two Jesuit priests, five Franciscan nuns, two Dominican nuns and a gaggle of Jesuit volunteers. I was, in fact, a member of the Jesuit Volunteer Corp. I've lived as a member of a very small minority in the dominant American society. What I've learned from my studies and from my life experiences is that what any society adopts as their way of life is arbitrary.

There are categories of elements that all societies share in common. Anthropologists refer to these general categories as cultural universals. Every society, for instance, has rules for defining relatives, for determining what is food and what shouldn't be eaten, who one can marry and what categories of people you are not allowed to marry. Interestingly, every society has beliefs about what happens to a person after they die. The fancy word for this is eschatology. The categories exist in every culture. They represent the questions that must be answered and the most basic human needs that every society must meet so that people can live and thrive in a stable group that can pass on this way of life from generation to generation. How the specific society answers those questions and meets those needs differs between every society. In our society, marrying a first cousin is frowned upon. In some societies, this class of relative is the preferred marriage partner. In some societies, eating pork is forbidden. In other societies, pork is a central part of the diet. Arbitrary.

The history behind the how and why a specific society adopts the elements of their culture as they do is a fascinating study. There's a lot involved in this process. Environment plays a central role, as a people have to make use of the resources they have available to them. Groups of people from the beginnings of humanity have borrowed from other groups. In fact, the easiest way to adopt a cultural element is to borrow it from neighboring groups. That's the reason why different groups of people who live close to each other share similar cultures. We might hate our neighbors, but if they've found a great way to start a fire, we're going to use it. Hey, we might be ignorant, but we're not stupid. Great people come up with some great ideas, and those become incorporated into a way of life. In the olden days, this was referred to as the Great Man Theory. Today it is probably called the Great Person of any Gender or Sexual Orientation Theory. I've lost touch with the literature. I'm reading novels, newspapers and articles about rare neuroimmune disorders.

The development and history of a culture is very complicated, and unique to that society.

It is naïve to think that underneath our differences, we are all alike. We are alike from about 30,000 feet. We all need to define food that we can eat, we need shelter from the elements, we need to find socially positive ways to reproduce and to have stable social structures that allow us to raise children while they are dependent and learning our complex cultures and languages. We are alike in so much as we have basic biological and social needs that cultures must meet. As we look closer at the differences between us, those become significant. We don’t think or believe the same ways. Those differences exist between societies around the world, and they exist in different societies within the United States. We are a nation of immigrants. With each generation, groups of people who have arrived here become more American. It has also been the case that important differences in communities remain based on nationality of origin, based on language, religion, values, social practices, festivals, music, food. Many differences remain and they do so for generations.

I was once in a conversation with a very close friend. I don't even remember the subject. She stated a point of view about something that was very important to her. My response must have been less than definitive. For a black and white kinda guy, I sure have a lot of grey in my life. She became aggravated with me, and with some exasperation and pleading in her voice exclaimed, you aren't a cultural relativist, are you? My response was, oh-oh. In many respects, I am. It's hard to be aware of the arbitrariness of culture and at the same time adhere to my culture like all of it derives from absolutes.

Cultural relativism is a fundamental concept in anthropology. It represents the ability to understand and appreciate a different culture, entirely on its own terms, its own history and development. If you use your own culture as a standard of judgement against which to compare a different way of life, you are going to have a very difficult time arriving at the meaning and appreciation of this different culture. Because, due to ethnocentrism, it will feel unnatural and wrong. And it is not. It is just different; as right, natural and beautiful as one's own and different way of life.

I can be relativist in the way I observe, respect and appreciate the differences between my people and our way of life, and those of other societies, and at the same time, have a set of values and beliefs that guide my behavior. Not everything is okay because it is done in a different society. It is okay for them ... it might not be okay for me at all. My background and life experiences make me less black and white about life than I would be otherwise. But I comfortably reside in a world with little confusion about values or what behaviors I need to resist in order to avoid shame, embarrassment and guilt. I just work a bit harder than someone who doesn't think about any of this, and I venture most don't.

They don't because people don't think about their way of life the way I'm describing. People are unconscious, for the most part, about their culture. People don't have an awareness about culture unless that way of life starts to change too rapidly or if it comes into conflict with a totally different way of life. That's a complicated proposition, and happens a lot in complex, industrialized societies that are culturally, ethnically diverse, such as our own. I will return to this idea shortly, because it is the source of so much of the discord we experience in our society.

For almost all human existence, people lived in isolated, homogeneous societies in which everyone shared the same way of life. They spoke the same language. They shared the same religious beliefs and rituals, the same values and world view, the same social, political and economic systems, the same kinship rules and socialization practices. They shared an entire way of life. As described above, people have always been suspicious or condescending or outright hostile to people who practice a different way of life, because it was wrong, unnatural and just plain yukky. We are the real humans. The others are not. This ethnocentrism is not just evidenced in the use of names which mean human beings or the real human beings. It can also be seen in the names that different groups apply to their neighbors. For instance, the word Eskimo is an Athabaskan word that refers to the Inuit peoples that means the raw meat eaters. It is not meant as a complimentary description.

Disliking or distrusting the other is a natural outcome of the way we learn, adopt and practice our culture. Feeling as though the other is less than human or not human happens because we feel as though our way of life is the only right way to think, believe and act.

When we lived in caves or small villages, ethnocentrism had minimal impact on the health and well-being of humanity. Groups were isolated from each other by choice. People avoided those who were different. They aren't the real humans like we are. Why would we want to be around them? Unless resources became scarce and competition for those resources created conflicts between groups, they stayed away from each other. And if conflicts did occur, the worse that happened was that someone got hit over the head with a stick or rock. People also developed relationships between neighboring groups for the purpose of trade. These were relationships developed by choice for the benefit and survival of the group. Oftentimes, these trading relationships were solidified by choosing marriage partners from the other group, because kinship relations are the strongest and most enduring relations. Marry out or die out. (Claude Levi-Strauss).

The development of cities and industrialization put an end to isolated and homogeneous societies. For the most part. You have to really get off the beaten path to find them, but please don't try to find them. They don’t want to be bothered, and they don't like you. There are also some people who lived on islands that have managed to stay fairly homogeneous.

The rest of us live in very diverse societies and have a real problem. Or as those with overwhelming optimism might say, we have a real opportunity. The natural outcome from learning a way of life leads to ethnocentrism, and this ethnocentrism causes all sorts of mayhem living in a society with people who practice so many different ways of life.

By the way, the diversity mayhem was exacerbated by Europeans sailing all over the world motivated by the desire to acquire (steal) the vast resources to be found in Asia, Africa the Middle East and the Americas. Like, hey, let's buy Greenland. Europeans divided up the world to pillage and drew geopolitical boundaries with absolutely no regard to the peoples who lived in all these places. They forced together tribes that had for centuries been isolated from each other, wanted nothing to do with each other, were suspicious of each other, and disliked each other. They were forced to form nations and governments and to cooperate with each other, all for the purpose of facilitating the pillaging. So many of the current conflicts in the world can be traced to this activity. We did this sort of thing in the United States in the way we managed the settlement of the hundreds of native tribes. We forced together tribes who had long-standing hostilities onto the same reservations or neighboring reservations and recommended that they start getting along with each other. All this activity derives from ignorance and/or greed or it is diabolical. Take your pick.

I'm going to focus on America, because that's where I live. We are a land of immigrants who came to this country from every society and culture on the face of the earth. People came by choice seeking economic opportunity and/or to escape prejudices and worse in their countries of origin. The only exceptions are the native tribes who lived here for thousands of years before anyone else arrived and the Africans who were forced into slavery here against their will. The rest of us came here from a society that practiced a different way of life.

How do you create a national American culture from the tremendous diversity of peoples coming to this land in such large numbers? The answer to that task was our public-school system. Likely more than any institution, our public-school system worked toward assimilating all these people who spoke different languages and practiced different cultures. The public-school system offered a homogeneous curriculum. If children didn't know English by the time they went to school, they were learning it in school. In addition to learning reading, writing and arithmetic, children recited the Pledge of Allegiance every morning at the start of classes and were immersed in American mythology, sometimes referred to as history in academic circles.

Over generations, we learned to love baseball, hot dogs. apple pie, and the Star Spangled Banner. We became patriotic and loved the ideals represented in the Bill of Rights and a free and open democratic society. We didn't have to learn ethnocentrism. Everyone brought it with them. When large numbers of Chinese made their way here, many found jobs building our railroads. They were different, and we were suspicious of them and didn't like them. When large waves of Irish or Italians arrived, we were suspicious of them and didn't like them, primarily because they were different. After the attacks on Pearl Harbor and the beginnings of World War II, we rounded up Japanese Americans and forced them into internment camps. Many of their sons, husbands, brothers served valiantly during the war. When the Jewish immigrants made their way here from all over Europe, no one needed any practice being suspicious and not liking the Jews. We had a 3,000-year history of not liking the Jews.

Prejudice is alive and well in American society. Racism is a cornerstone of the American ideology. Antisemitism continues to exist as it has for thousands of years. I so naively thought that we were living in the golden age of Let's Just Let the Jews Live in Peace in America. I am so disappointed, and a bit more than concerned, that I was wrong.

Prejudice means just that - judging before knowledge or without knowledge. Prejudice involves the application of characteristics to a group of people that have no basis in reality. These preconceived judgments are thoughts and beliefs. Prejudice exists in people's minds. When we act on those preconceived ideas, that is discrimination. When we judge a group and then behave in a way to disadvantage a person who belongs to that group or the entire group, that is discrimination.

In our more recent years, we've turned our focus of prejudice towards Muslims and Hispanics. We haven't forgotten our prejudices towards everyone else; these are just the groups who have received more of our attention. If you are ever confused about our prejudices, take a gander at who Hollywood makes the villains in action films. It’s the American litmus test for who we are suspicious of and don’t like this week.

I'm going to build a wall and Mexico is going to pay for it. Nothing new here; just a bit less subtle than the customary bigotry that is fundamental to American culture. While we've wanted to keep all newcomers out, we rarely come up with such an explicit symbol as a wall. Our walls, our prejudices and discrimination, are often manifested in less tangible ways, i.e., we ordinarily rely on strict immigration policies or by making people totally miserable and unwelcome about being here. On the misery index, taking children away from their parents and putting them into cages, has to rank right up there.

The great irony in all of this is that we are all newcomers. Only the native American tribes can stake claim to being the indigenous peoples. The rest of us our immigrants. And every generation of immigrants has, in their own way, wanted to close the door on the next generation of immigrants. That notion also is as American as baseball and apple pie.

Mexicans or Colombians come to America because they live in poverty and only see a future for themselves and their families with the economic opportunity we promise in America. Or they feel compelled to escape to America because they fear for their lives or the health and well-being of their families. Hispanics are not drug lords. Hispanic peoples are coming to America for all the same reasons people want to come and have come from everywhere in the world. They come here for the same reasons you came here or your family came here.

Hi Sandy, I really appreciated this illustrated anthropology course, despite the difficulty linked to the language and to the fact that I, in the past,only studied at the University the interactions between marine animals, but which, ultimately, are not that different from those observed between human groups. I appreciated that you quote Claude Lévi-Strauss, of whom I really liked "Tristes Tropiques"

Regarding the Holocaust, which you mention at length at the beginning of this article, this is a central event in European history in the 20th century. Born in 1962 in France, I must cope with an often schizophrenic French historical narrative: French police officers actively chased and arrested Jews to deliver them to the Nazi occupier. At the same…